The campaign in Bristol

Bristol was the first city outside of London to set up a committee for the abolition of the slave trade. This was in 1788, following Thomas Clarkson’s visit to collect evidence against the slave trade. Clarkson was the driving force behind the campaign for Abolition. The first public meeting was held on 28 January, and resolved to establish a committee, collect money for the cause and start a petition. Many of the members of the committee were Quakers with family slaving connections. The Bristol Quaker Harry Gandy had captained a slave ship in his youth, and likewise Joseph Harford’s family had long exported kettles from their brassworks in Bristol to West Africa. Supporters at that first meeting included the Aldermen (City officer ranking next to the mayor) George Daubeny and John Harris. Daubeny’s family had investments in sugar refining. The Committee approached the government about the slave trade, held meetings, and circulated petitions. They ensured that the Bristol papers were full of poems and letters condemning the slave trade.

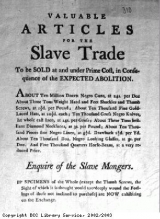

Some 800 people volunteered to sign the first Bristol petition against the slave trade in 1788. This was one of the first political campaigns in which women were allowed to be involved! They played an active role – especially in the boycott of slave-produced sugar. Various tactics were used by the Abolitionists to get their message across to the wider public. One example was the production of leaflets such as the one pictured here, which was a spoof advertisement for Valuable Articles of the Slave Trade. The ‘articles’, or items, which it mentions would be of no use to anyone once the slave trade was abolished. ‘about Ten Million Dozen Negro Guns … About Three Tons Weight Hand and Feet Shackles and Thumb Screws …’. Negro guns were usually cheap or second-hand guns used for trade with Africa. Hand, feet shackles and thumb screws would have been used for restraining the enslaved Africans once they were bought.

Nonconformist Christians (that is, members of religious bodies which had split from the Church of England) led the anti-slavery campaign locally. They were given a boost by Thomas Clarkson’s visit in 1787. He was the main force behind the movement and inspired local people to become involved. Clarkson found that, generally, Bristolians were not in favour of the slave trade. About Bristol, he observed that ‘everybody seemed to execrate [hate] it, though no one thought of its abolition.’ So people in Bristol criticised the slave trade, but no one did anything to end it. People might have been afraid of the possible economic effects on the city should the slave trade be abolished.

The Yorkshire MP William Wilberforce, the public face of the Abolition campaign, came to Bristol in 1791 to encourage the local campaign. Olaudah Equiano, a well-known former slave who wrote and campaigned against slavery and the slave trade, planned to visit Bristol to promote the cause. The Bristol poets Robert Southey, William Wordsworth, Hannah More, Anne Yearsley and Samuel Coleridge all wrote against the trade. Southey wrote dramatically in a poem called Sonnet III about sugar. It was the main product made by slaves and was boycotted by people (that is, they purposely stopped buying it in protest against the slave trade). Southey wrote about tea drinkers: ‘Oh ye who at your ease Sip the blood-sweeten’d beverage!’. The blood the poet refers to is that of the slaves who grew the sugar. John Wesley, who founded the Methodist church, wrote against slavery. He preached against the trade in his church, the New Rooms, in Broadmead, Bristol, where he attracted large congregations of rich and poor people.

Pictured here is the Bristol poet Anne Yearsley who was also a campaigner for the abolition of the slave trade. Ann Yearsley was a milk seller who educated herself. Amongst her writings were poems on Bristol’s trade in slaves. One reads ‘ … when I sell a son, sweet Heavens, let it be my own … ‘. The poet is saying to God, that if she had to sell a child, it would be better if it were her own, rather than that of another woman. It is a criticism of the buying and selling of African children in slavery.

Also pictured is the writer Hannah More. This influential Bristolian began her career as a playwright, and founded a school for young ladies in Park Street. She became an Evangelical Christian in her later years, establishing Sunday Schools, writing religious tracts and campaigning against the slave trade. Her poems against the slave trade, such as The Sorrows of Yamba, or the Negro Woman’s Lamentation, were widely read.