Page 266 of 352 pages « First < 264 265 266 267 268 > Last »

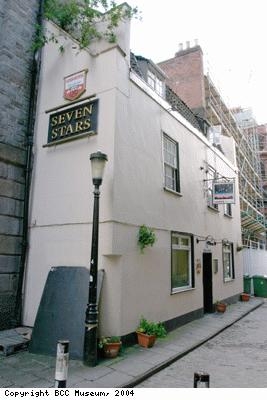

Historic site, Seven Stars Pub

Description:

Historic site, Seven Stars Pub, near Victoria Street, Bristol. In the late 1780s the Quaker anti-slavery campaigner, Thomas Clarkson, visited this pub when investigating Bristol’s involvement in the slave trade. It is reported that the landlord refused

to associate with the slave ship captains and crew. He showed Clarkson around other pubs that helped recruit sailors for the trade. Clarkson uncovered the awful conditions suffered by British sailors as well as the horrendous suffering of the slaves themselves.

Initially public disgust of the slave trade stemmed from learning about the sailors’ plight, rather than that of the slaves. Eventually the anti-slavery campaigns used both the sailors’ and the slaves’ experiences as evidence against the trade.Clarkson looked at Muster Rolls (sources of information about the crew on ships). From these he found that the death rates of Bristol slave-ship crews were very heavy in comparison to other cities involved in the slave trade.

With thanks to the authors of the Slave Trade Trail around Central Bristol, Madge Dresser, Caletta Jordan, Doreen Taylor.

Creator: David Emeney

Date: 2004

Copyright: Copyright BCC Museum

Historic Site, Theatre Royal

Description:

Photograph of Historic Site, Theatre Royal. This is England’s oldest working theatre, opened in 1766. The original 50 financial investors, each gave £50 towards the building. Many of them were members of the Society of Merchant Venturers , a Bristol organisation for merchants which still exists today. Other investors in the theatre included the Farrs, a family of ropemakers and slave traders (later the owners of Blaise Castle Estate), Henry Bright and Michael Miller, who all lived in Queen Square and were participants in the African trade. Another financial investor, George Daubeny (Bristol’s mayor in 1786), was a sugar refiner and glass manufacturer, who lobbied for an end to the slave trade, then changed his mind and joined the opposing committee in 1789.

With thanks to the authors of the Slave Trade Trail around Central Bristol, Madge Dresser, Caletta Jordan, Doreen Taylor.

Creator: David Emeney

Date: 18th century

Copyright: Copyright BCC Museum

Historic site, Marsh Street

Description:

Historic site, Marsh Street. This was once a rough area near the quayside, the haunt of seamen and, by the 18th century, of poor Irish migrants. The anti-slavery campaigner Thomas Clarkson wrote in 1808 that Bristol slave ship captains would get crew for their slave ships in the mainly Irish-owned public houses there. The pubs were known for their music, dancing, rioting, drunkenness and profane swearing . There are said to have been some 37 public houses on this street alone. In the 1820s one such pub, The Fortunes of War , featured a figure of a sailor with a wooden leg, loading the gunpowder into a cannon. Opposite this public house was once the bonded sugar warehouse of Messrs Robert Bird and Son.

With thanks to the authors of the Slave Trade Trail around Central Bristol, Madge Dresser, Caletta Jordan, Doreen Taylor.

Date: 2003

Copyright: Copyright BCC Museum

Historic site, The American Consulate.

Description:

Photograph of Historic site, The American Consulate. On the south side of Queen’s Square is the site of the first American Consulate in Britain, established in 1792, to protect the interests of American citizens in Bristol. Between 1698 and 1807 about 2,100 slaving voyages sailed from Bristol. Trade with Africa, the Caribbean and America accounted for over half of Bristol’s trading in the 18th century. After American independence, Bristol continued to trade with both the northern states and southern slave states of America. This explains the establishment of a consulate in Bristol to represent American interests in the city. Slave-produced tobacco from the southern states of America were important to the city’s economy.

With thanks to the authors of the Slave Trade Trail around Central Bristol, Madge Dresser, Caletta Jordan, Doreen Taylor.

Creator: David Emeney

Date: 18th century

Copyright: Copyright BCC Museum

Historic site, 33-35 Queen Square

Description:

Historic site, 33-35 Queen Square. A plaque commemorates Captain Woodes Rogers, 1679-1732, who was an early resident of the square. He was Bristol’s most famous privateer, which means he captained ships that were privately owned but given permission to fight in wars by the government.Rogers was celebrated for his voyage around the world from 1708 to 1711. Woodes Rogers had many investments including the slave ship Whet stone Gally , which in 1708 took 270 African slaves to Jamaica in the Caribbean. As a privateer, he helped to keep the Caribbean under British rule against the Spanish who fought them for it. In 1717, at his own suggestion, he was rewarded for his efforts and made governor of the Bahamas in the Caribbean, where he ended his days.

With thanks to the authors of the Slave Trade Trail around Central Bristol, Madge Dresser, Caletta Jordan, Doreen Taylor.

Creator: David Emeney

Date: 18th Century

Copyright: Copyright BCC Museum

Historic site, 29 Queen Square

Description:

Photograph of Historic site, 29 Queen Square. Now the regional headquarters of English Heritage, this is the best preserved of the original buildings in Queen Square, as shown by its forecourt gates and railings and its internal panelling and staircase. The house was built in 1709 for Alderman Nathaniel Day, who became Bristol’s mayor in 1737. Day petitioned against a proposed tax on slaves. By mid-century, number 29 was the home of Henry Bright, one time mayor of Bristol, a prominent merchant and slave trader. On his death in 1771 he left an annuity [or allowance] of 10 pounds per annum, chargeable on the house where I now dwell, to my black servant, Bristol.

With thanks to the authors of the Slave Trade Trail around Central Bristol, Madge Dresser, Caletta Jordan, Doreen Taylor.

Creator: David Emeney

Date: 18th Century

Copyright: Copyright BCC Museum

Historic site, Queen Square

Description:

Photograph of Historic site, Queen Square. Queen Square was completed in 1727, when Bristol’s involvement with the slave trade was nearing its height. The square shows the kind of lifestyle held by Bristol’s merchants and officials, made possible by wealth from the trade with Africa and the Caribbean, much of which invloved trading in slaves and slave-produced goods. Less than a third of the original buildings remain however, mainly owing to damage caused by the Bristol Reform Bill riots of 1831 and the Second World War. In 1775 seven Africa merchants, one Caribbean merchant and a firm of Virginia tobacco merchants were based here. Christopher Claxton was one Queen Square resident. He was an activist campaigning for the continuation of slavery. During the 1831 riots about the changes to the voting system,Claxton’s black servant refused to join the rioters. He was said to have thrown some of them out of the window of his master’s house. By the early 19th century merchants had left the square for the wealthier district of Clifton, away from the smells of the river and the threat of flooding.

With thanks to the authors of the Slave Trade Trail around Central Bristol, Madge Dresser, Caletta Jordan, Doreen Taylor.

Creator: David Emeney

Date: 2003

Copyright: Copyright BCC Museum

Historic site, The Hole in the Wall Pub

Description:

Photograph of Historic site, The Hole in the Wall Pub. Once called the Coach and Horses, the Hole in the Wall pub on the corner of Queen Square is a well known Bristol landmark. In the 18th century it was one of a number of pubs frequented by seamen in the times when sailors could be kidnapped by press-gangs during wartime and forcibly recruited into serving in the British Navy. The spy house on the dock side of the pub was reputedly used to watch out for press-gangs as well as for government agents searching for smugglers. Although press-gangs were not used for slave ships, underhand methods were employed to get sailors aboard. (Slave ships were not popular with sailors because of the high death rates among the crew, and the danger of slave rebellions.) It was common in many of the taverns around the centre of Bristol for landlords to receive money from ship owners in return for getting sailors drunk in order to get them into debt. The only way sailors could then avoid going to the poor house or debtors’ prison was to work onboard a slave ship.

With thanks to the authors of the Slave Trade Trail around Central Bristol, Madge Dresser, Caletta Jordan, Doreen Taylor.

Creator: David Emeney

Date: 2003

Copyright: Copyright BCC Museum

Historic site, Quakers Burial Ground

Description:

Photograph of Historic site, Quakers Burial Ground, off Redcliffe Hill. A plaque proclaims this as the original burial ground for the Society of Friends, better known as the Quakers (who were a religious group which spilt away from the Church of England). As a close-knit religious group, Quakers usually married amongst themselves and entered into business ventures together. As a result, a complex international network of family, banking and buisness partnerships spanned Britain, Ireland, America and the Caribbean in the 18th century.

In the late-17th and early-18th centuries, Bristol Quakers such as Charles and John Scandrett were slave ship owners. Famous Quakers who benefited from the produce of slave labour included Frys (cocoa) and Lloyds and Barclays (banking/insurance for ships), and the Galtons (guns). Other families, less known today but leading Bristol merchants of the period, including the Champions, the Goldneys and the Harfords, whose brass and iron goods were traded to West Africa for slaves.

By the 1760’s Quakers became the first religious body to oppose the slave trade. Quaker women were particularly active in this campaign. By the 1780s the Quakers were at the forefront of the movement to stop the slave trade. They went on to make an important contribution to the final campaign in the early 19th century which sought to free all slaves in the British colonies.

With thanks to the authors of the Slave Trade Trail around Central Bristol, Madge Dresser, Caletta Jordan, Doreen Taylor.

Chocolate was first used as a drink, sweetened with sugar to mask the bitter flavour of the chocolate. Later it was used for making eating chocolate. At this period, most people drank beer, wine or spirits. Water was not safe to drink, tea coffee and chocolate were expensive. Quakers promoted drinking chocolate as an alternative to alcohol.

Creator: David Emeney

Date: 2003

Copyright: Copyright BCC Museum

Historic site, Guinea Street

Description:

Historic site, Guinea Street. A guinea is a gold coin, named after the West African coast, known as the Guinea coast, from which so much gold came from.Some guinea coins featured an elephant castle, the emblem of the Royal African Company. This London-based trading company had control over the English trade in gold, ivory and slaves on the coast of West Africa until 1698.

The house at the end of the row (nos 10-12) was owned by a merchant and sea captain, Captain Edmund Saunders. He was responsible for 20 slaving voyages and was also a warden at St Mary Redcliffe Church between 1732 and 1739. In 1759 Joseph Holbrook, another sea captain resident in the street, offered a handsome reward for anyone capturing a negro man, named Thomas, a native of the island of Jamaica …5’6” high, speaks good English and wears a brown wig. A sugar house on the corner of lower Guinea Street was set up in 1797, one of a number in this area.

With thanks to the authors of the Slave Trade Trail around Central Bristol, Madge Dresser, Caletta Jordan, Doreen Taylor.

The language used to describe people of African descent in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries is unacceptable in today’s terms. We cannot avoid using this language in its original context. To change the words would impose 20th century attitudes on history.

Copyright: Copyright BCC Museum

Page 266 of 352 pages « First < 264 265 266 267 268 > Last »