The 19th century until the present day

Many of the black people living in Bristol in the 18th century married into Bristol families. Over the course of a few generations, their descendants ‘disappeared’ into the population of the city. It has been estimated that one in five Britons has a black ancestor from the 17th or 18th centuries.

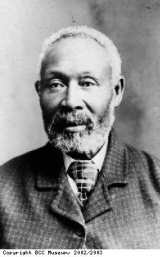

After the end of the slave trade in 1807 and of the status of slave in 1834, few black people came to Bristol. At least, there are few records of any coming. One young man, Henry Parker, arrived in Bristol in the 1850s. He had been a slave on an American plantation (slavery was not abolished in America until 1865, following the American Civil War). He ran away, and was helped by a Quaker family to reach Boston in the northern state of Massachussetts in America. The northern states in America were against slavery, and so people would help slaves fleeing from the southern states to escape. Black and white people helped to run the ‘Underground Railroad’, a system of safe houses and routes to the northern states and Canada. Henry Parker got work on a ship from Boston, and eventually came to Bristol. He found lodgings and work, and married a Bristol woman. His wife taught him to read and write, and he became a lay preacher at the Hook’s Mill Church (now the Ivy Church) on Ashley Hill in the St Werburgh’s district of Bristol. His eldest daughter Emma married an Irishman, James Head. They had 16 daughters. Some of the descendants of Henry Parker still live in the Bristol area. Pictured here are Henry Parker and two of his granddaughters.

The First World War of 1914-18 saw many men in the British colonies (such as Jamaica in the Caribbean) joining the British army and navy to fight for Britain, the ‘mother country’. From the Caribbean and Africa, men joined the local regiments and fought on the side of Britain in Africa and Europe. Many of those wounded were brought to Britain for medical treatment. After the war finished, many of the African and Caribbean regiments were brought to Britain for the demobilisation process, to be ‘retired’ from the forces and re-enter civilian life. Many decided to stay. The heroism of the black soldiers and sailors was soon forgotten. They were often subject to racist attacks, and unable to find work. The Second World War (1939-45) saw the men and women of the colonies and the Commonwealth again join the army, navy and air force to help the ‘mother country’. One young man, pictured here, was U F G Walcott, who joined Royal Air Force Bomber Command as an Airman in 1944. He was from Barbados in the Caribbean, and served in the Royal Air Force (RAF) to the end of the war. He settled in Bristol after he left the RAF. He worked as an engineer and was active in community societies. In 1970, he was appointed as a Justice of the Peace, to sit in judgement on cases in the Magistrates’ Courts.

About 16,000 people of African-Caribbean descent live in Bristol today (black and dual descent). Most came to the city in the 1950s. At that time the British government invited people from the British colonies to come to this country to live and work. There was a shortage of workers after the war and it was felt this might help the economy. People came to Britain from India and Pakistan, and Ghana and Nigeria in West Africa. They also came from the islands of Jamaica, Barbados, St.Kitts, Nevis, Dominica & elsewhere in the Caribbean. The SS Empire Windrush was the boat that brought the first migrants from the Caribbean to work in Britain, in 1948. Many of those who came to Bristol found lodgings in the St Pauls area of the city. The bombing of the nearby city centre during the war meant that residents who could move out to the safer suburbs did so. After the war refurbishment of the bombed houses was held up because plans for the area were not decided or did not go ahead. Houses might be pulled down in the future for redevelopment, so no one wanted to buy them or do them up. This meant that immigrants who came from the Caribbean on the ship the Windrush and later, found housing in St Pauls that they could afford as they established themselves in a new country.

Immigrants who came from the Caribbean to Britian on the Windrush ship have become known as the ‘Windrush generation’. They are now the elders of the community. Their grandchildren and great-grandchildren are now growing up in Bristol. Tony Forbes is a young artist of African-Caribbean descent who was born and bred in Bristol. The painting shown here was commissioned by Bristol Museums and Art Gallery for the exhibition A Respectable Trade? Bristol & The Transatlantic Slave Trade. It reflects his view of growing up in the city. “I really love this city. I was born in St Pauls and grew up on a white council estate called Southmead. There are things about Bristol I’m proud of, but…”. The artist was not proud of the city’s slaving past or the way that it was ignored until recently. Nor was he proud of the racism that ran through institutions in the city. “What I am trying to show in the painting are some of the things I don’t want to see happening to the next generation of kids, black or white. We have to live together.”