Plantation Owners

Many of the earliest British plantation owners were from Bristol and the West Country. The Bristol merchant Colonel George Standfast, for example, established a plantation producing sugar in Barbados in the Caribbean by the 1650s. His son employed 238 enslaved Africans by 1679. Sir John Yeamans, who once lived at Redland Court in Bristol, was one of the early settlers to prosper on the Caribbean island of Barbados. He owned a sugar plantation in Barbados and established a colony in South Carolina, America, where slaves were used. Yeamans’ brother Robert (pictured here) was the Sheriff, Mayor and Chief Magistrate of Bristol, as well as a merchant who had an early involvement in the Caribbean trade. John Dukinfield, from Bristol was a slave trader and member of the Society of Merchant Venturers, an elite body of Bristol merchants involved in overseas trade. His son, Robert, was left a large slave plantation by his father, in Jamaica in the 1750s. There were a number of Bristol plantation owners on the tiny island of Nevis, in the Caribbean. The wealthy Pinney family was amongst them. The Bristol-based porcelain manufacturer Richard Champion retired to own a slave plantation in South Carolina, America, when he failed to gain a political position in Britain.

Merchants also owned plantations. They would sometimes end up taking over plantations because they had leant money to cash-poor plantation owners. The owners would later fail to repay their loans, leaving the merchant as the owner of the plantation. Many plantation owners did not live on the plantations and depended on a range of managers to live there and run them. An early example of such a landlord was William Helyar, who lived in East Coker, Somerset but owned Begbrook plantation on the Caribbean island of Jamaica. In the 1680s, Helyar employed the Bristol merchant William Swymmer to provide him with slaves. Swymmer’s brother Anthony was a merchant in Jamaica and the family ended up owning plantations there. Robert Dukinfield, who owned Duckinfield Hall, in Jamaica, did live on his plantation. Owners who lived on their plantations were required to take part in the local government of their island, and Dukinfield was a member of the colonial Assembly which ran Jamaica.

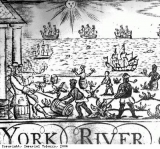

Plantation owners and their managers might purchase the slaves brought across from Africa directly from the captains of slave ships. The captains would sell the enslaved Africans to the plantation owners who would use them to work on their land. Enslaved Africans were usually purchased through companies that specialised in selling them, such as slave dealers Smith and Baillies on the Caribbean island of St. Kitts. Before the slave ships left Bristol, their owners would contact agents or slave dealers in the Caribbean. These dealers would then sell the slaves once the ship had arrived there from Africa. The image from a tobacconist’s business card, pictured here, shows an early representation of a plantation. The owner can be seen sitting in the shade, smoking his own tobacco and watching his slaves as they gather in the tobacco harvest. Plantation owners were not the only customers who wanted to buy slaves. Many people in the cities of North America, including New York, Charleston and Providence in Rhode Island on the east coast, employed enslaved Africans as domestic servants, sailors and construction workers.